Báyò Akómoláfé takes us on a journey toward the rewilding of thought and practice. Against critique, beyond method, he weaves paraontologically in a logic that defies any binary structure. The mode of approach: a politics of blackness that errs the pathways, moving beyond those “slushy standpoints” that are “the ecological burdens of moral positions, perceptions, and judgments… the invisible effects – pre-dating us and spilling beyond us – of being morally composed in specific ways” toward movements of thought that lets in the “chimeric, mycelial, promiscuities that aerate the soils of our ongoing becoming.” In exile from our-selves. “When the very idea of territory becomes relative, nuances appear in the legitimacy of territorial possession” (Glissant, 1997, p.15). To err in a politics of exile, in a blackness continuously remaking itself, is “to turn,” to attune to the turn through which the very notion of territory, of history, of identity, turns from milk to butter.

The turn does not deny the path taken. Butter is always also milk. But it does carry, in the turn, a certain quality of a transformation, a transduction. The butter is, to some degree, a derivative of milk, a surplus value of flow of its potential. Because surplus value of flow, or, when potentializing it from the angle of life-living, what Massumi also calls surplus value of life, is that quality that cannot be reduced to the sum of its parts. You can’t make milk out of butter. The derivative force of the more-than does its work in more than one mode. Speculative pragmatism reminds us that all comings-to-be include the potential as yet unexpressed that nonetheless makes a difference.

In the erring, there is never a denial of origins, but there is a question of whether they were as territorially grounded, as ontologically precise, as we imagined them to be. Is there ever a map that takes us back to an origin? Partition-logic is powerful.

“Four days away from the Christmas of 1848, in the dark and occultic hours before morning wakes, Ellen and William Craft beheld each other through tearful eyes for the last time. Minutes later, they collapsed to the floor, both falling into a writhing heap of limbs and agony, convulsing, trembling, and flailing until the strong brew they had ingested hours earlier passed through them. When the sun yawned awake to the sounds of the cock crow, his surveillant gaze travelled across the undulating fields of Georgia, across the cottonfields of one plantation in Macon, and fell through the cracks of the cabin where two lovers had spent their last human moments, and where a few obsidian-black feathers belonging to two fugitive crows now littered the log floor – tell-tale signs of a daring escape, a transformation too offensive for history to embrace.

But they were not the first to turn, you see.” (Akómoláfé 2023)

To turn: to departition, to sill experience.

To turn: to be in the movement of a certain quality of grace.

In the hard-and-fast politics of diversity that knows in advance who is included, a subject is made in advance of any movement. This is what Báyò teaches us. But what Báyò also teaches is that there is a counterpoint to the enforced stabilization of the account of who counts, a counterpoint that syncopates, that rhythms subjectivity, that produces it. This counterpoint is the turn.

To turn is not simply to transform. Or, it is not simply to move along a line that bequeathes a certain variation. To turn is to skirt time’s line, to curl its presuppositions. To turn is to catch the grace of a movement-moving, and to move into its bend.

Grace cannot be produced. It is not a volitional act. Grace is what appears, what scintillates, at time’s crossing, at that emergent interstice where past and future coincide to make time, to make worlds.

If grace is the ease in the moving of an erasure of before and after, a preaccelerating into the futurity of time’s emergent rhythm, it is also a kind of freedom.

This freedom is not Saidiya Hartman’s “burdened individuality of freedom.” It is not the neoliberal promise to continue to produce one’s value according to emancipation’s wager. It is not the “reward of the good citizen.” That freedom – “the hope for disembarkation, the myth of arrival, the slushy idea that seems innocuous at first but then travels when one least expects it and builds a parking lot where there was once a sacred mountain” – won’t do, as Báyò writes.

“We need a new problem. New bodies. New rituals.”

Grace moves us into a concept of freedom that is made not of burdened individuality but of the turn’s own making, infraconsciously. Freedom is not the ability to turn, the gesture of turning. Freedom is the turn itself, the graceful act of a metamorphosis that changes the world in its wake. Because a graceful movement is just that – a movement that carries the seeds of a certain memory of the future, a movement that moves the past in just this way. Bothatonce.

This notion of grace and its adjacency freedom are both Bergsonian concepts. Bergson is here thinking in terms of planes of movement at their infrathin differential, of times in overlap, of movements moving. He is thinking of the being of relation, to use Glissant’s beautiful phrase, of life-living at the interstices of worlds at the cusp.

The freedom of which Bergson writes moves at the pace of infrathin resonances. In the turn, a deja-felt colours the shape the event took, but the ineffability of the vista as it now emerges prevents any strong contours. An aftertaste, an afterglow, yes, but content itself eluded. It’s not that once we were slaves and then we were crows. The planes of life-living are meshed, a bird-becoming always on the cusp.

The burdened individuality of freedom wants to hold life to content. It wants to know with certainty where we come from and where we go. It wants to safeguard difference so that diversity can be checked, and checkmarked. It wants to know for sure what we became to ensure we always stay the same.

But there is no self-same. Bergson gives an account of freedom’s force through music. When we listen to music, he explains, a certain parsing occurs through which the music’s qualitative nuance is diminished. To hear the differential of music’s immanent rhythms, to participate directly in the quality of its sounding, it is necessary to hold back the conscious ordering of sensation. For Bergson, this means doing away with the idea that sensation can be measured, which also means: articulated, identified, parsed. Parsing, so allied with the neurotypical, not only reduces our capacity to feel the complexity of the event in the event, it perpetuates the hierarchy of conscious experience over nonconscious experience, reason over affect.

Freedom is the felt-effect of a change of quality through which new modes of perception become possible. Freedom is how the event expresses its complexity, in the event.

Freedom requires that activity is kept in the act. When this is the case, volition is repositioned as an aspect of experience, active in the act, no longer the external director of experience mediated. Without a hierarchy of conscious versus nonconscious experience, a more complex compositional field of experience emerges. Here there is still room for mutation, for difference, for an opening toward the as-yet-unseen, the as-yet-unthought, the as-yet unfelt. This is freedom, for Bergson, defined against the usual definition of the free act which would separate freedom from the in-act, placing freedom side by side with a voluntarist notion of decision. Such a definition of freedom has us standing outside the event. We are free because we are rational, because we orient the act, because we have agency, because we resist the affective forces of our passions and desires. In this usual definition of freedom, as Bergson says, “we give a mechanical explanation of a fact, and then substitute the explanation for the fact itself” (Bergson, 1913, p.181). As he writes, “time is not a line along which one can pass again” and therefore “freedom must be sought in a certain shade or quality of the action itself and not in the relation of this act to what it is not or to what it might have been” (Bergson, 1913, 181-183).

Freedom is the turn, or better said, its grace. Freedom is the act’s quality, the ethos in the act’s opening onto experience. Not all events are free, but in every event we find the germs of freedom.

As we now turn to Báyò, perhaps we leave freedom behind and return to grace. Because some concepts are simply too worn out to do new work, and freedom may well be one of those. But as we move in the grace of time’s differential, we are changed. In the curve, a concept of blackness practices a refusal of any kind of adequation. No binary is possible. In the being of relation, whiteness loses its hold. This is where we begin, and where we will always need to begin again.

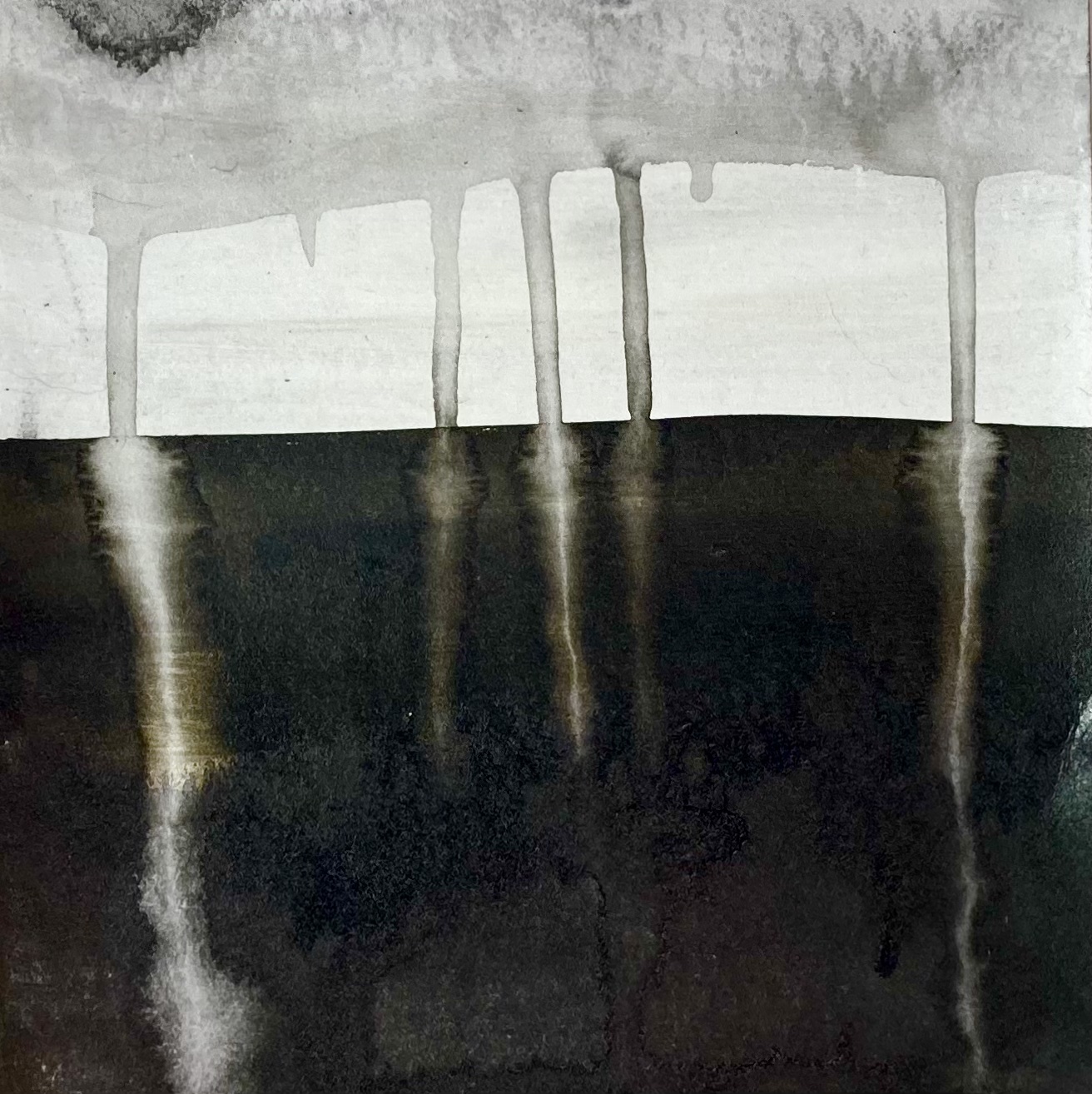

Art by Krista Dragomer.